Caption: A service provider with the Visiting Nurse Association & Hospice of the Southwest Region monitors in-home patient care.

By Danielle M. Crosier, Vermont Maturity Magazine.

RUTLAND — For nearly 80 years, the Visiting Nurse Association & Hospice of the Southwest Region (VNAHSR) has been providing a wide range of care options and supports for Vermonters with chronic or terminal illnesses, delivering service “with compassion, dependability, and expertise” to people of all ages.

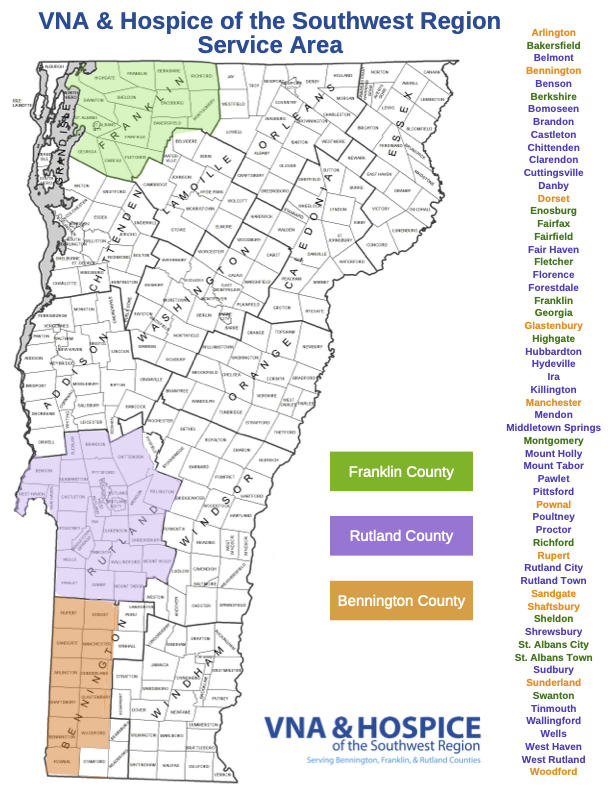

The non-profit, Medicare-certified, home health and hospice organization was originally founded in Rutland County and has since expanded to include “about 90%” of Bennington County and, more recently, Franklin County.

“We first started in 1946 in Rutland City,” recounted Chief Clinical Operations Officer Nicole Moran, “and then, in the 90s, we acquired hospice in Bennington County. And then, we acquired Dorset Nurses Association. In 2014, we acquired Bennington VNA; in 2017, we acquired Manchester; and then, in 2024, we acquired Franklin County. The mission is the same, and it’s to get the best community service and community healthcare out there – to as many people as we can that need it.”

The acquisition of Franklin County will lead to a name change and rebranding campaign in the future, Moran teased, as the name Visiting Nurse Association & Hospice of the Southwest Region no longer rings true.

“Franklin County is not in Southwest Vermont; the name doesn’t apply anymore,” laughed Moran, but declined to reveal the proposed name change just yet. Whatever the new name will be, and whatever the revised mission statement will read, it will emphasize care.

Employing approximately 75 caregivers dedicated strictly to hospice throughout the state – nurses, physical therapists, occupation therapists, speech language pathologists, social workers, spiritual care workers, aides, nurse practitioners, and medical doctors – VNAHSR is one of the state’s largest non-profit home health and hospice providers.

With four main branches in Rutland, Bennington, Manchester, and now St. Albans, each branch follows the same protocols and procedures, with subtle differences based on the territory served and the varying staffing models that are based on volume.

Caption: The care and support that is provided by members of the Visiting Nurse Association & Hospice of the Southwest Region is comprehensive and holistic.

Moran, who is not simply an administrator but who also has extensive expertise in patient care, worries about whether those in the communities that VNAHSR services fully understand the role that hospice can play in end of life care. And, she worries for good reason.

“Hospice,” said Moran, “it’s so underutilized and, because the length of stay for hospice patients is so low, we would love to see patients referred to hospice earlier, so that they get that full benefit.”

“And, we want to convey to the community the importance of having conversations about end of life, particularly advanced care planning and where hospice can kind of support and allow patients to die with dignity and peace – and in wherever place they call home,” explained Moran.

However, Moran expressed concern that conversations on death and dying are often “like the elephant in the room.” They’re uncomfortable. They’re awkward, and they’re ebay to push aside. There is an avoidance of conversations about end of life wishes, choices, and care plans – and that is troublesome. Moran believes that the avoidance of these conversations is prevalent in our culture – not just the culture of Vermonters, but for us as a nation. For Moran, she believes that it simply represents hope.

“No one wants to talk about death and dying,” said Moran, gazing out the window of her corner office in Rutland. Outside, the warm breeze was wrestling with the bows of the trees, the grasses in the field. “We’re all going to die, you know? We’re all terminal. But, we can’t talk about it as a culture. And, I think there’s a lot of reasons why. Our medical system is so heavily focused on fix, cure, treat. Fix. Cure. Treat. Throw medicine at it. Throw a treatment at it. And, it feels almost never ending. I think people assume that there’s always going to be one more treatment to do. There’s going to be one more medicine to try. And, I think providers in general aren’t good about having those conversations early on in the disease process.”

Providing the example of congestive heart failure, Moran noted that the caregivers of VNAHSR bear witness to this “very common diagnosis.”

“We see that a lot,” said Moran. “It’s a terminal illness, but it can last upwards of 10 years.”

What Moran would like to see is for providers to have that initial conversation at diagnosis, and say, “this is a disease that we can treat – but you will eventually succumb to it,” rather than fixating the conversation so heavily on treatment options. That in itself is a difficult conversation to have. Perhaps an even more difficult one to have, though, is with family members and chosen caregivers.

Pulling from her time as a nurse in the intensive care units (ICUs) of Rutland Regional and Dartmouth, Moran knows the story well, “It just feels like there’s always something else to try.”

Now, in her role with VNAHSR, Moran wonders how to make that cultural shift – that shift that says, “It’s okay to plan for letting go, and it’s okay to talk about dying.”

“The statistic is that something like 75% of people want to die in their own home,” explained Moran. “The reality is that very few die in their own home. So – how can we shift that culture, and get people to start having these important conversations.”

Caption: A service provider with the Visiting Nurse Association & Hospice of the Southwest Region monitors in-home patient care.

What Moran would like to see happen is for the dialogue to open, even if it feels uncomfortable at first. Moran would like to see that dialogue open for everyone, no matter their age or health.

“Getting people to talk about what they want and what they don’t, what they wouldn’t want in different scenarios, is important. Advanced care planning, getting your wishes on paper and also talking about it, is so important,” said Moran, adding that what we want at one stage of life can change as we age. “What I want right now at 44 is probably different than what I’m going to want at 74. So, I think getting people comfortable with the fact that we are all going to die – and that none of us are immortal – and identifying what’s important.”

“If that’s being at home, dying with dignity and respect and surrounded by the people and the things that they love – then, you know – that’s where hospice comes in.”

According to Moran, hospice is underutilized across the country – specifically in the state of Vermont.

Caption: Map of current VNAHSR service area.

“Our utilization is about 42% of patients that would have been eligible to actually receive the service,” said Moran, shaking her head, and adding that she believes it is because people are largely unaware of what the organization does, are unaware of how to access it, or have not had those initial conversations with family and friends and potential healthcare proxies.

“We often get that referral for hospice at that 11th hour,” pointed out Moran, “and that’s when patients are actually dying – whereas hospice can be for six months, or longer. Being a caregiver is challenging, said Moran, and when that falls solely on the individuals and their families, it places an undue burden upon them.

There are eligibility criteria, Moran said, and anyone can put in a call to hospice for an assessment.

“Ultimately, it should be the providers having that communication,” pointed out Moran. “And, ultimately – in order to admit a patient to hospice – we have to have that provider order. However, families can reach out to us, and ask us to do an evaluation. Sometimes, a provider is not going to see what we see. We see a fair number of people advocating for themselves, or for a family member. They just say, ‘I would like someone to come out and evaluate my mom, or my sister, for hospice care.’ And, we do evaluations visits and assessments free of charge.”

The assessment would entail a nurse visit to the home, and a thorough one-on-one evaluation, “So, the nurse will go out and do that head to toe physical assessment and talk about the goals of care, what’s important to them and then, obviously, compare that with their medical eligibility – based on their diagnosis.”

If the evaluation shows that the individual is “not quite ready,” Moran said, VNAHSR staff will then continue to check in, keeping that individual and family on their radar, and touching base from time to time to see how things are progressing. But, Moran pointed out, “At least a family member can have a point person.”

Additionally, the organization has been lucky to find partners with another home health and hospice organization in Rutland, where the two companies can provide unbranded and collaborative educational outreach to the community. This outreach helps to inform the population of the work the two companies are doing, the services offered, and how to access them. It also helps open up that conversation about advanced care planning.

There is also a lot of misinformation out there, Moran stated, and she fears that it further complicates the message. Many people believe, she said, that hospice is “a place that people go to die.”

“In the State of Vermont, there is only one hospice facility – and it’s in Colchester, Vermont. But, hospice can be in your own home, or wherever you feel you want to die. Most people want to die in their own homes, but the challenge is making sure that they have the support, the equipment, the medications that they need to be comfortable up until the end – and that’s where hospice comes in. It includes all of those things – medications, hospital bed, oxygen, wheelchair, commode, etc.”

It’s relieving the family caregivers from navigating those challenges that can make all the difference, especially when it comes to providing high quality end of life care. VNAHSR staff are as well versed in navigating the healthcare system as they are in providing compassionate and experienced care.

“Access to the hospice benefit is a right for every patient,” added Moran, “and we encourage people to ask those questions and advocate for themselves.”

Caring for those in hospice care involves many deep conversations, added Moran. It involves a lot of question-asking – especially questions that involve the individual’s readiness to enter that last phase of life. Trained care providers can guide individuals through the process to ensure that it supports whatever the wishes of the patient are. These conversations involve medical decision-making, end of life supports, counseling for the patient and the family, and more.

According to Moran, many people want to fight that fight right until the very end. Others, fed up with the discomfort of prolonged treatments, simply want peace of mind – to “wave that white flag,” so to speak.

“To wave the white flag is to say that you are ready to accept the fate that has been given to you, and that you want to allow nature to take its course and use the tools that hospice can provide to help guide you through that,” said Moran. Those tools revolve around the expertise of care that hospice specializes in. “Nursing, obviously, is a big part of the hospice benefit, specifically managing symptoms and helping educate family members and the patient on how to effectively manage whatever symptoms they’re having.”

Other tools involve trained social workers, to help with any sort of psychosocial stressors, “You know, family dynamics are always fun, and they get even more fun at the end of life. I mean, I think when stress is high, people react very differently. So, how can we support that patient in the family from that perspective, helping them gain access to resources if they need it, like long term care benefits through Medicaid, spiritual support, etc.”

Moran noted that spiritual support is different for everyone, “It doesn’t have to be religious. I mean, my spiritual environment is outdoors. That’s where I go. Helping people connect with that, identifying any conflicts and helping guide them through that – that’s what hospice can do.”

In addition, hospice services are supervised by a specialized provider, “We have a medical director that oversees all of our hospice patients, and they help guide and support the treatments that we do for the pain and the symptoms – so guiding us as far as medication dosing, and helping us determine what that patient needs to be comfortable.”

Moran asks people to close their eyes in this moment – and ask themselves what would happen if they suddenly lost the ability to make health care decisions for themselves. Who would know what they wanted, and who would they want making those decisions? That is the planning that needs to take place now, Moran said, and those are the conversations that need to be had. And, knowing when to make that call to hospice for planning or care is also important.

“[Hospice care] is unique in the fact that it’s probably the only sector of healthcare that is so individualized, and so comprehensive and holistic at the same time,” said Moran. “We have a lot of ability to adjust the plan of care based on what the patient needs. And, that’s one of the great benefits – it’s not cookie cutter, you know? It’s really focused on that patient and the family and helping them identify their goals – and helping them get there. And that flexibility that we have is, I think, probably one of the greatest strengths of the hospice program.”

To find out more about the hospice care and planning that VNAHSR offers, visit https://www.vermontvisitingnurses.org/hospice-care/.

Comment here